The ideal scoring set up: Choosing judges

Written By Akim Mansaray and Sherman Charles

Graphics by Akim Mansaray and Sherman Charles

When deciding on a scoring set up for your contest, there are several things to consider, such as the scoresheet, judges, and awards, just to name a few. Regardless, the primary focus must be fostering educational goals and developmental progress. Artistic performance assessment is understandably difficult because of the varied views and the subjective factors that impact performance curricula. Thus, the goal of this blog post is to lay out what needs to be considered to have a quality, transparent contest with integrity where education is the prize.

The following four posts discuss 1) Choosing scoresheet categories, 2) Caption weights and calculating results, 3) Choosing judges, and 4) Awards and time penalties. This post is the third of the four. If you have any questions about this post’s content, or if you would like to share your view on this topic, feel free to add your comments at the bottom of this page. Don’t forget to read the other three posts!

Choosing Judges

The first item to be concerned with when hiring judges is conflict of interest. One must ensure that no one on the judging panel has any skin in the game – they are not associated in any way whatsoever, whether as a clinician, choreographer, or professional acquaintance, with any of the groups they are evaluating. Perhaps you did this to the best of your ability, but you find out during your contest that one of the judges worked with one of the competing groups. While there isn’t much you can do at this point, it’s not the end of the world. First, if the judges have not yet started scoring groups, then go ahead and remove that judge from the panel – they can function as a clinician if you would like, either in person or over tapes. If they have already started scoring groups, then ask the rest of the judges if they are ok with averaging their scores to stand in as the “disqualified” judge, just for the group with which they have conflicts of interest. They can score normally for all other groups. Lastly, although this is the least preferable of your options, you could notify all of the competing directors and get their feedback – just be prepared for what they might say. Although, for the most part, judges tend to be honest regardless of whom they are evaluating, taking the step to remove any possible conflict of interest maintains the integrity and transparency of the contest, and a contest that is trustworthy and accountable is a contest that attracts new participation and retains past participants.

While it certainly is cost effective to hire local judges, judges from outside of the region can provide new perspectives on performances, particularly toward the end of a competition season. Most competitors attend local contests for most if not all of their season. As a result, one group may see the same handful of judges week after week and the comments and feedback can become stagnant. This isn’t to say that it always does. In fact, seeing the same judge week to week could be an advantage since they will see how any given group learns from their feedback and improves the performance. However, new eyes and ears will be able to catch different elements and nuances of a performance and provide valuable praise and criticism. So, it is important to have a mix of familiar and unfamiliar judges on your panel.

Not only is it important to consider the degree of familiarity and novelty when selecting judges, one must also consider expertise. This might seem like a relatively simple, no-brainer consideration to make, but this factor can have several levels to it. One that has already been alluded to above is the fact that all judges should have a professional understanding of the performance that they are evaluating. This does not mean that the judges must have a degree or title, but rather they must have clout and recognition for the role that they play in the community. Former and current directors, choreographers, arrangers, etc. are obvious choices. Up and coming judges that are beginning their careers should be limited to relatively low-stakes or lower skill level contests for the sake of providing accurate, honest, and informed feedback to all participants. Once they gain some experience, they can move up to higher level divisions. As a result, make sure you have a mix of old and new blood in your panel, and please incorporate beginners in your process to help foster good judging habits.

While hiring a judge that is a performer or a member of an artistic community adjacent to the one pertinent to your contest (e.g., stage or film actor, recording artist, local performer, etc.) could be a valuable and attractive decision, once again, one must take care in ensuring they are accustomed to the nuances and particulars of the art form that they will be evaluating. We have seen marching band directors judging showchoir even though they have no experience or association with any showchoirs at all! Not only was the judge uncomfortable with this, the participants were as well, and as a result, the quality and integrity of the contest diminished. If you decide to go this route, be 100% certain they will provide valuable educational feedback to all of the participants.

A factor that many are unaware of or simply ignore is matching your judges to your scoresheet and your scoring method. If you would like your judges to evaluate the entire scoresheet, one has to ensure that each judge is capable and willing to do so. We have come across several vocally oriented judges who have been tasked with scoring choreography, yet they have no business doing so nor or are they comfortable with it. The opposite is true as well. This isn't to say that judges that are capable of scoring a full sheet don’t exist – they most certainly do. The simplest way to avoid this is to assign judges to specific captions rather than asking them to score the full sheet. For example, judges who are (only) choreographers should be limited to captions relevant to choreography while judges who are (only) vocal directors should be limited to vocal captions. However, with this approach, the scoring method and the desired proportions/weightings of captions determine exactly how many judges per caption you should have.

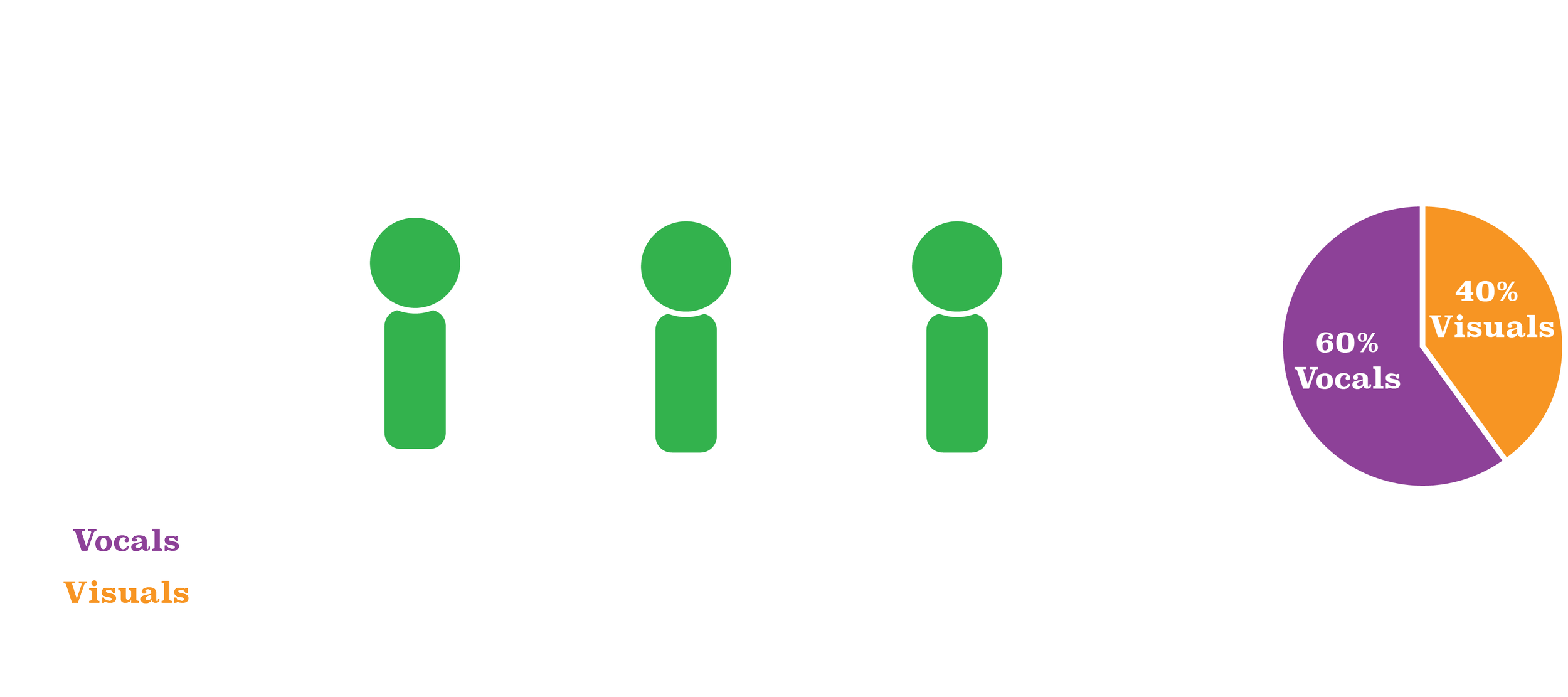

Using the scenario above, we have two captions, Vocals and Visuals, and we want Vocals to be worth 60% and Visuals to be 40% of the final score. If you are using Raw Scores (which you shouldn’t) you need to make sure that the total possible combined scores of all of the judges result in the desired ratio between captions. For example, our hypothetical scoresheet has 60 possible points in Vocals and 40 possible points in Visuals. There are two ways to preserve the desired 60/40 ratio: 1) all judges score the full sheet;

or 2) there is an equal number of Vocal and Visual judges, perhaps two of each as illustrated below.

The second option is less ideal because it is prone to ties, both because there is an even number of judges and because they are split by caption.

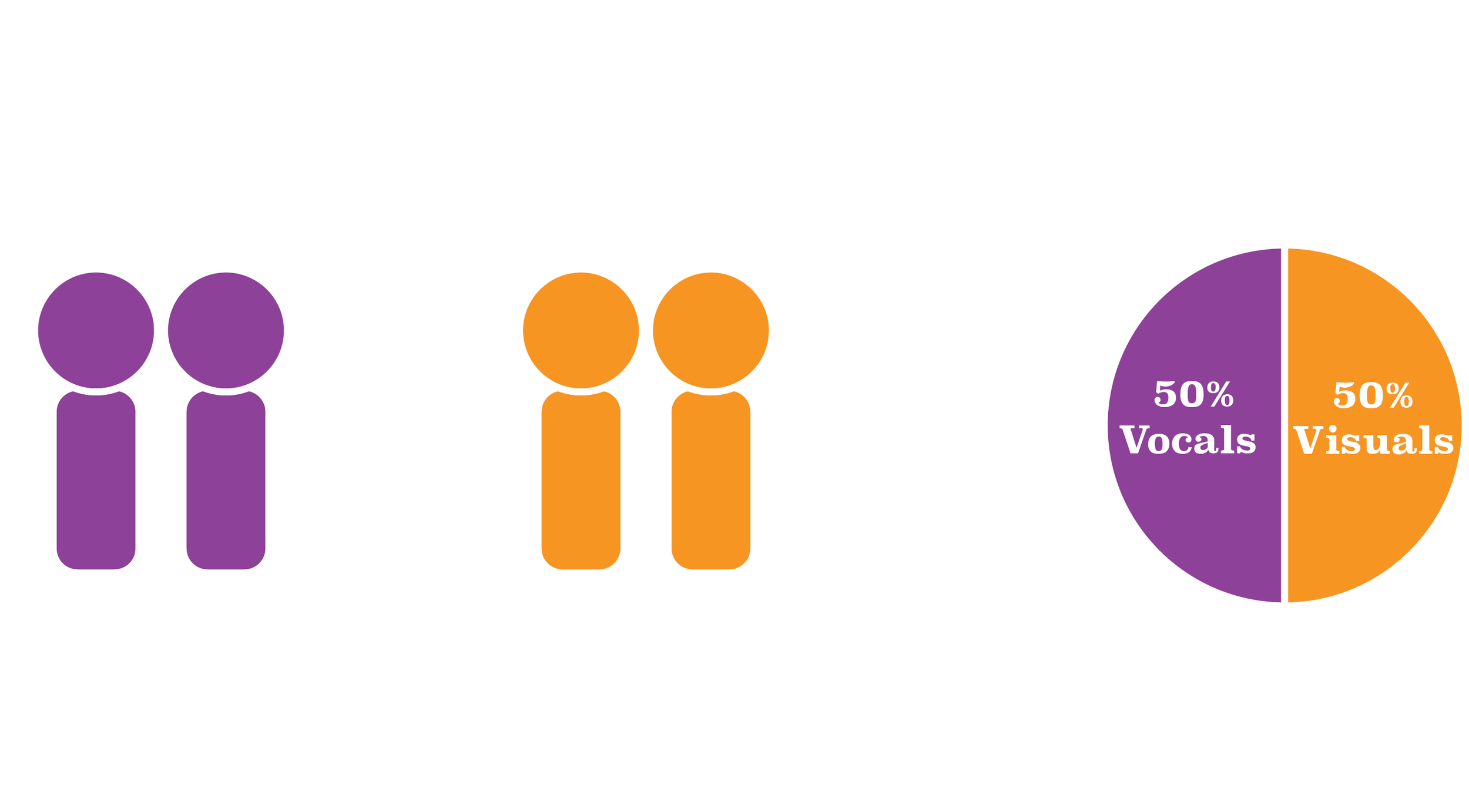

The scenario changes slightly if you decide to use a scoring method that converts to rank (e.g., Condorcet), which you should. Instead of proportioning the total possible points, you must proportion your judges and the captions that they score. Otherwise, you could be unintentionally creating an undesired weight, such as the one shown below.

If your judges are scoring the full scoresheet (both Vocals and Visuals), then you can have as few as 3 or as many judges as you would like—but try to have an odd number—and your proportion will be preserved. If your judges are split by caption, you must have a minimum of 3 Vocal judges and 2 Visual judges in order to preserve the proportion, as is shown below.

With this format, all judges have an equal voice, they are evaluating elements that they are qualified to judge, and we get the desired caption weighting for the final results. In our opinion, this is the ideal judging panel set up. If five judges is simply out of your price range, three is the absolute minimum number of judges for group performance evaluations and at a number this low, all three should be qualified to judge and assigned to all captions on a scoresheet.

Rogue Judges – The odd one out

Over the last decade and a half of doing scoring for showchoir contests all around the United States, we have appreciated the importance of mitigating the impact of a judge that diverges from the rest in an extreme and unexpected way. Let’s assume that at your contest you have every reason to believe all of your judges are honest, ethical, and professional, but one of your judges is the odd one out. Some differences are expected, but one just seems out of sync with the others by a large margin. Maybe they have a participant in last place that everyone else has in first or second. This might seem like a disaster, but choices that are made prior to the start of the contest about the scoring method specifically can save you from damage control and the headache from the complaints that you will receive. We are specifically referring to methods that convert to rank and mitigate the effect one judge can have on the final results. We won’t spend a lot of time on this topic here since you can read about scoring methods in, Consensus Scoring Methods: Lessons from the French Revolution, but the short of it is the Condorcet method is absolutely the best method to do exactly this.

What do you do about elements of a show that are not performed by students?

This is not pertinent to all types of performances, but it is particularly prevalent in showchoir, specifically the showband that accompanies the choir. At any given contest, there might be performances that are accompanied by a pre-recorded track, a live band composed of students, or a live band of professional instrumentalists. Whatever the case may be, all of them are competing against each other, so what role does the band play on a scoresheet, if any? We are under the philosophy that the accompaniment is indeed part of the show and should contribute to a group’s overall score. However, it should not be a deciding factor in the final standings. We recommend that no more than 10% of the scoresheet should be dedicated to the accompaniment. In addition, directors and students still want feedback on the showband, especially if the players are students. Thus, it is a good idea to have one judge that scores a separate sheet solely dedicated to the band. This sheet should have the same types of categories that are described in the first blog post of this series – those that have educational value for the directors and students. If you have a Best Band award, it should be determined by these scores, and professional bands and recorded tracks should not qualify for the award.

Recommended Reading

Much of what is written above is inspired by the following publications. We encourage you all to take the time to read through these thoughtful papers to gain better insight into music assessment, its purpose, its value, and its intended outcomes. You can find many of them by simply searching for them in your favorite search engine or clicking the links below.

Kim, S. Y. (2000). Group Differences in Piano Performance Evaluation by Experienced and Inexperienced Judges. Contributions to Music Education, 27(2), 23–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24127075

Smith, B. R. (2004). Five Judges’ Evaluation of Audiotaped String Performance in International Competition. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 160, 61–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319219